www.Jasimuddin.org

1.Pat and Patua important audio-visual mediums 2.Gazir Gan, Pat, puthi Pat 3.Manasa Mangal ritual 4. A tradition which ridicules the clash of civilisations 5. Civilisations are built on the exchange and encounter of different cultural traditions 6.Save 'Patachitra''scroll painting- Our National Heritage 7. Save Traditional Bengali Dolls Our National HeritagePat-chitra culture

"Many years ago I collected different types of quilts, dolls , 'Patachitra' 'scroll painting , Pat Patua, Gazir Pat - scroll pictures of Gazi, Monosa , pupet, alpana etc from different villages of Bengal. Friends advised me to make an exhibition. Gaba da displayed the items beautifully at the roof of Rabinra Nath Tagore's Jorashako House. Rabinranath Tagore carefully observed all the items and Abinranath Tagore was overwhelmed with the exhibition. Rabinranath Tagore said that I want to keep an exhibition of folk culture at Santiniketan. My collection began to increase day by day and I did have any space to keep the collection. I asked again Rabinranath Tagore to receive the collection for Santiniketan. He said he would ask Nandolal Basu to collect the items. But Nandolal Basu did not show any interest!

Rabinra Nath Tagores comments on folk culture and painting was published in the news papers. I have made several exhibitions at Calcutta University (Department of Archeology), Institute Hall. During summer vacation I left the collection in a box at Azinra Nath Tagore's house but when I came back from Faridpur, my box was no more there (1932). Today I still remember those unforgetable treasures of bengali folk culture.

Jasim Uddin, Thakur Barir Anginay, At Tagore's Premise, 1963

1. Pat and Patua important audio-visual mediums in educating the masses since immortal

There is a very deep cultural link the Indo-Gangetic civilisation, such as that of terra-cotta, cloth and natural fibre like jute, "shola" and beetle nut bark fibre, which are on the verge of extinction. These items go back to as much as 12 centuries. The Moenjodaro link which is visible in our terracotta dolls and toys go back to 3,000 years. Not only has that history been forgotten but the realisation that they are diminishing is that within two decades they'll be there no more. "One craft in particular which has suffered as recently as in 15 years is the type of painted scroll called 'Ghazir pott'. Ghazi is a 'pir' recognized both by the Hindus and Muslims, by the woodcutters, honey gatherers, fishermen and boatmen in the Sundarbans. They invoke the Ghazi pir, the tiger personality who protects the people who enter the jungle."

In Bengali, "Pat" means "scroll" and "Patua" or "Chitrakar" means "Painter". The origin of the painted scrolls is very ancient. We could find some in the Pharaohs' graves in Egypt. In India the first description of these painted scrolls can be found in a sacred text dated 200 B.C.

Pata art is of two kinds - art on broad sheet of folded cloth and eye-art on short piece of fabric. The fabric in fact makes the base for pat art. Clay, cow-dung and some sticky elements are skillfully sprouted on the fabric. When dried, the fabric becomes tough but mellow enough for sustaining the stroke of the artist's brushes. Pata artists draw on it religious motifs, such as gods and goddesses, Puranic stories, slokas, etc. The pictures illustrate the religious and spiritual symbols the folk society likes. Kailas, Brndaban, Oudh and other holy places of the Hindus usually appeared in the pata art. This art form flourished particularly during the Buddhist period in Bengal. The pata art carried the life sketch of the Buddha and of his sayings and anecdotes. The Buddhist monks traded on pata arts very extensively. From the eighth century onward, the pata tradition was taken over by the Hindus. Yadu, Yama, chandi, ten incarnates, deeds of Rama, loves of Krsna, Gazi etc became the themes of Hindu pata art.

A narrative type of folk painting is still being practised by a particular chitrakar (Painter) community in West Bengal (India) and in Bangladesh. Its origin is unknown. The origin of the chitrakar community too remains a matter of speculationThe style too is handed down the generations. Patua, Patidar, Pata are the names by which a chitrakar is commonly known. He is a poet-painter-singer. He rhymes a narration around an episode of some Hindu mythology that imparts a moral lesson. He paints the sequences in a series of rectangular frames in vertical format as a scroll painting. To the clientele, he unfurls the scroll frame by frame as his narration set to tune proceeds. The moral lesson makes listeners aware of the vices and virtues of life.

The training in the handed down style includes memorisation of set patterns, lines, colours, and the poses and postures of the trends left by the forefathers. Despite some limitations, the style shows unique formal simplification and superb colour orchestration. It features all the traditional qualities of Bengal folk art. This art is addressed to a culturally homogeneous public that is accustomed to the images. It is painted on paper or on starched cloth.

Nowadays, this art form is still used mainly in the West Bengal, Bihar states and Bangladesh. The main centres of pata art were Dhaka, Noakhali, Mymensingh and Rajshahi in Bangladesh, and Birbhum, Bankura, Nadia, Murshidabad, Hughli and Midnapur in West Bengal. In West Bengal, the painters are also singers. The scrolls are done with sheets of paper sewn together and sometimes stuck on canvas. Their width can go from 4 to 14 inches and their length, seldom below 3 feet can exceed 15 feet. A piece of bamboo, sometimes carved, is placed on each extremity of the scroll and is used to roll and unroll the painting which is done with vegetal colours : charcoal or burnt rice for the black, betel for the red, a fruit from the Nilmoni tree for the blue colour, etc... In order to fix the colours, they add a tree resin which they first melted.

The story is shown in sequence, like a story board or a comic strip. Seldom are the scrolls with text.

The Patua is a kind of minstrel. He goes from village to village, with a bag containing several scrolls. He gathers together the villagers around him and unrolls his paintings never showing more than 2 or 3 images at a time, and he sings the painted story. Then the villagers give him some rice and rupees. This way the Patua earns his life.Painted scrolls have been used in Bengal in eastern India for centuries as a means of telling religious stories and also of informing people about important current events. Although today even the smallest village is likely to have access to televised news, this tradition continues in the villages of West Bengal not far from Kolkata.

Major events, whether local or global, become subjects for painted scrolls - recent examples have been the Asian tsunami, the Gujarati earthquake, and the assassination of Indira Gandhi, as well as broader subjects such as birth control and the spread of AIDS. The scrolls, a long strip of paper backed with cloth and painted in registers are carried from village to village by their painters and are unrolled before an audience, to the accompaniment of songs which tell the story of the events depicted.

The attacks on New York on September 11th 2001 quickly became the subject of scroll paintings. This one, acquired from the artist, Madhu Chitrakar, in 2005, was painted in the village of West Medinipur in West Bengal in about 2004. Painted scroll depicting the September 11 attacks on New YorkThe 'Ghazir pot' is a series of folk stories told by the village men of the bravery of this man who protected them from tigers. Ghazi, she said, is sacred to the Hindus too as they have a similar personality whom they called 'Shatta pir' but he rides a leopard while Ghazi rides a tiger and both carry symbols in their hands."

One important reason for the diminishing of crafts is that the metropolis dwellers are not paying according to the demand of the producers. When the villagers are putting the products into the market the price is cut to half and bargaining goes on. The elite are least bothered while the middle class like the items and wish to use them at home but unless one is a connoisseur of art the people of the upper echelons of society have forgotten village crafts altogether

"People are ready to pay a high price for painting but they are not ready to pay for a craft that has taken six months whereas the painting may have been done in three days. When a woman has worked on her handicraft on an authentic design for half a year she has the right to ask for more.

The reason why our standard has fallen is because the rural artisans have difficulty in marketing their products. I have sometimes gone to a source, following a 15 year-old documentation, and then discovered that in Rajshahi where 'Shokh hari' was being done village-wise is now confined to a few solitary houses. Similarly the makers of blanket from lamb's wool cease to function as before and take up other means of income generating sources. I found only an old widow still pursuing that craft." Chandan said that the entire Bangladeshi scenario is the same. He said that the folk art craftsmen have abandoned their old skilled work due to lack of demand in the market and plastic for instance has replaced clay. The only exception, he pointed out, was Naogaon where nine instead of four families are following a 'sholar' craft making birds and other items since the last 15 years. Even there is a problem as the craftsmen got the material for nothing but now the landlord are charging them a fee for the raw material, Chandan said (Daily Star, October10, 2004).

Ghazir Pott - Oldest Audio-Visual Medium

Gazir Pat Pats (Sanskrit Patta) means picture is an ancient folk tradition. Dr. D. P. Ghosh (1980) describes , " Two thousand and five hundred years ago, scroll-painting or panel painting was widely used in many parts of India as mass media for enjoyment, general education and religious practices." Ram pats or Ghazi pats (picture) used by Hindu and Muslims. Pats are held very vertically and painted from top to bottom were shown scene after scene from the epilical stories.pats were produced for educative and religious purposes. They are used as accessories of balled singer.. Patua is a composer, artist and singer. Evidences of this has been cited through the last two thousand and five hundreds years that Pat and Patua were important audio-visual mediums in educating the masses almost corresponding to the gallery lectures of modern museums.

Gazi Pats Ballad:

Jamdud kaludt at

The right and left

The friend of the Jam raja (king)

Sits in the midst

Gazi says: Chase them away

With Gazi's name.

Gazir Pot

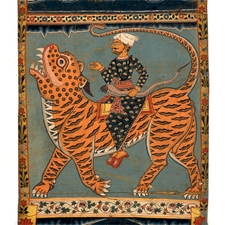

Shambhu Acharya can trace his interest in arts and crafts back to nine generations (450 years). His family did paintings of not only Gazir Pot (scrolls illustrating the myth of the Muslim saint Gazi) but Mahabharata, Ramayana, Behula- Lokhindor Kahini, Sri Krishna and Muharram Pot (based on the life of Hussain and Hassan). A pat, Shongho explains, is a story, and a potobhumi is a series of stories that revolve around a hero. Shambhu does stories of both Hindus and Muslims. Gazi, he says, the subject of many of his paintings was a powerful Muslim general with a metaphysical force, who tamed wild animals, and has a following among the gypsies. He is specially associated with the tiger and is often presented as riding a tiger. He was revered by both Hindus and Muslims and had an assistant called Kalu. Shongho has done 27 panel paintings with Gazi as his subject. He makes his canvases by layering markin cloth with brick powder, tamarind juice and egg yolk. He has also used various oxides and black soot.

Today he has 24 panels on the subject of the freedom struggle and hopes to exhibit these in Dhaka. He has brought in the freedom effort of the Bangalis during the British rule and later during the time of the Pakistani supremacy. He has brought in Titumir, Pritilata, Surjo Sen and Dudu Mia. He has depicted Mahatma Gandhi, Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Bongobondu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The Language Movement of 1952 has not been left out. Each panel, 5ft by2 ft, has taken him 12 days. The delineation has followed the folk style that one found in the Gazir pot collection, that had been exhibited in 2003 at Chitrak.

Some of the work has been done outdoors and some inside the house. He did the base with a piece of tied up cloth dipped in colours. Next with brushes he added the fine lines in black, red and other colours. Apart from ambitious subjects, he has also dealt with the conventional topics of fishermen, farmers and women dressing and doing their hair. The conventional folk forms have been incorporated and these have his distinctive style. He did try oil colours but he did not feel comfortable with this medium.

He had no problems in selling his paintings as he had the support of Ramendu Majumdar of ad firm Expressions and he had access to Chitrak gallery. This presentation of folk stories with paint on cloth is unique. Shambhu's parents used to make traditional statues out of clay and Shambhu had studied them. "However, the work of my parents followed the Hindu custom while I wanted to bring in subjects that would interest the Muslims as well," Shambhu says. With the presentation of the subject of the freedom fighters, Shambu hopes to continue with the preservation of traditional art in Bangladesh (Fayza Haq, February 10, 2005). .

2.Gazir Gan, Pat, Puthi Pat

Today, many of us are ignorant of Gazir Gaan, Gazir Yatra, Gazir Pat, Puthi Pat, Kiccha-Kahini jari and so on and on. Saymon Zakaria has been travelling to different parts of Bangladesh to find out and let others know of what remains of the indigenous cultural performances, which still survive like the flickering light of a burnt away candle.

Gazir Pat- Scroll Painting - Method

Gazir Pat a form of scroll painting; an important genre of folk art, practised by patuyas (painters) in rural areas and depicting various incidents in the life of Gazi Pir. Until the recent past, the narration of the story of Gazi Pir with the help of a Gazir pat was a popular form of entertainment in rural areas, especially in greater Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla, Noakhali, Faridpur, Jessore, Khulna and Rajshahi. Those who took part in the performance were members of the bedey community and Muslim by faith. Besides Gazir pat, there were other scrolls depicting well-known stories such as Manasa Pat (based on the goddess manasa), Ramayana Pat (based on ramachandra), Krishna Pat (based on Lord krishna) etc. The asutosh museum of indian art (Kolkata, India), Gurusaday Dutt Museum (Kolkata, India) and the Museum

Gazir pat is usually 4'8" long and 1'10" wide and made of thick cotton fabric. The entire scroll is divided into 25 panels. Of these, the central panel is about12" high and 20.25" wide. There are four rows of panels above and three rows below the central panel. The bottom row contains three panels, each of which is5.25" high and 6.25" wide. The central panel depicts Gazi Pir seated on a tiger, flanked by Manik Pir and Kalu. The central panel of the second row shows Pir Gazi's son, Fakir, playing a nakara. The central panel of the third row shows Gazi's sister, Laksmi, with her carrier owl. The right panel of the second row shows the goddess Ganga riding a crocodile. In the bottom row, Yamadut and Kaladut, the messengers of Yama, are shown in the left and right panels. The central panel shows Yama's mother punishing the transgressor by cooking his head in a pot. As Gazi Pir is believed to have the power to control animals, a Gazir pat also depicts a number of tigers.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines, and small circles) are often used. The figures lack grace and softness. Some of the forms (such as trees, the Gazi's mace, the tasbih, (the Muslim rosary), birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, Kalu, Manik Pir, Yama's messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. There is no attempt at realism. The traditional method of painting Gazir pat begins with the preparation of size from tamarind seeds and wood-apple. The tamarind seeds are first roasted and left to soak overnight in water. In the morning the seeds are peeled, and the white kernels are ground and boiled with water into a paste. The paste is then sieved through a gamchha (indigenous towel). The tamarind size thus obtained is then mixed with fine brick powder. In order to prepare wood-apple size, a few green wood-apples are cut up and left to soak overnight in water. The resultant liquid is strained in the morning, and the size is ready to use.

A Gazir pat is generally painted on coarse cotton cloth. The piece on which the painting is to be executed is spread on a mat in the sun. A single coat of the mixture of tamarind size and brick powder is then applied on the side to be painted, either by hand or with a brush made of jute fibre. After it has dried, two coats of size are applied on the other side of the cloth, which is then left to dry. On the side to be painted, another coat of a mixture of tamarind size and chalk powder is applied. When the cloth is dry, it is divided into panels with the help of a mixture prepared with wood-apple size and chalk powder. When the prepared cloth is dry, the patuya starts painting the figures.

The pigments were originally obtained from various natural sources: black was obtained by holding an earthen plate over a burning torch, white from conch shells, red from sindur (vermilion powder), yellow from turmeric, dull yellow from gopimati (a type of yellowish clay), blue from indigo. The patuya would make the brush himself with sheep or goat hair. Some of these techniques are still used today. However, the patuya usually buys paints and brushes from the market.

The tradition of Gazir pat can be traced back to the 7th century, if not earlier. The panels on Yama's messengers and his mother appear to be linked to the ancient Yama-pat (performance with scroll painting of Yama). It is also possible that the scroll paintings of Bangladesh are linked to the traditional pictorial art of continental India of the pre-Buddhist and pre-Ajanta epochs, and of Tibet, Nepal, China and Japan of later times. [Shahnaz Husne Jahan]

The scroll paintings of Gazir pat (pat meaning cloth), present the valour of legendary figure Gazi Pir, who was respected and worshiped as a warrior-saint, writes Robab Rosan Although worshipping the images of Gazir Pir is not mentioned in history, according to some scholars, the Muslim saint Gazi, might have appeared around the 15th century and seemed to be related to the rise of Sufism in Bengal. Islam Gazi, a Muslim general, served Sultan Barbak (1459-74) in Delhi and conquered Orissa and Kamrup (now Assam). Towards the end of the 16th century, Shaikh Faizullah praised the valour and spiritual qualities of this general in his verse Gazi Bijoy, the victory of Gazi.

There are some influences of Khijir Pir or Khawaj Khijir, a Muslim holly man considered as the protector of water, found in the story of Gazi Pir. To the worshipers of Gazi, this warrior-saint protected his devotees from attacks of wild animals and demons in the forests. In Bangladesh, particularly, in the regions of the Sundarban, the story and images of Gazi Pir had earned much popularity among the forest dwellers, like woodcutters, beekeepers and others. These communities still believe in the supernatural powers of the Pir and utter his name when they venture in to the forest.

In the plains, Gazi is worshiped as the protector against demons and harmful deities and saves them from all sorts of dangers. The villagers usually call the gayens or folksingers, who know the story of Gazi Pir to sing the saint’s praise. The travelling storytellers, mostly belonging to the bede (gypsy) community, use a Gazir pat and pointing at the images on the pat, they narrate the power and prowess of the Pir in their singing verses. The devotees also hang the scroll paintings of Gazi in their houses to protect them from the influences of evil power.

The singers’ preaching created a demand for the pats among the devotees, irrespective of caste, creed and community and the pats had gained a huge popularity in the rural areas across the country, in the early years. Traditionally, the singers were Muslims while the patuas belonged to the Hindu religion. Sadly, at present, this combined form of art, paintings on pats and rendering of Gazir praise, has lost its purpose as a savoir from evil.

Gazir pat, though being considered as a nearly extinct art form, is gaining new ground. There were many patuas — hereditary painters of pats —who once existed in many regions of Bangladesh; now the number has drastically reduced. Until the recent past, the narration of the story of Gazi Pir with the help of a Gazir pat was a popular form of entertainment in rural areas, especially in greater Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Comilla, Noakhali, Faridpur, Jessore, Khulna and Rajshahi.

Gazir pat has specific images painted on a single canvas which have remained unchanged through the centuries. These images have been honoured as sacred symbols of good omen. There are twenty seven panels in a traditional Gazir pat, which measures 60 inches X 22 inches. The ankaiya (painter) follows the traditional styles in depicting the images. In the twenty-seven panels, the ankiya draws the images of a shimul tree; a cow; drum to depict triumph of Kalu Gazi; sawdagar or merchant; a deer being slaughtered; Asha or hope, the symbol of Gazi; Kahelia; Andura and Khandura; tiger; umbrella in the hand of Gazi’s disciple; Suk and Sari birds sitting on the umbrella; Lakhmi; charka, the spinning wheel; two witches; goala or milkman; mother of the goala; a cow and a tiger; an old woman beautifying herself; Baksila; Ganga; Jamdut; Kaldut; mother of Jam raja; and in the centre Gazi riding on a tiger. The singer or singers narrate sometimes the night long story, pointing at the characters, which appear in the twenty seven panels of the pat.

Red and blue are the two pigments mainly used in the pats. There are slight variations of colour, with crimson and pink from red, and grey and sky-blue from blue. Every figure is flat and two-dimensional. In order to bring in variety, various abstract designs (such as diagonal, vertical and horizontal lines and small circles) are often used. Trees, Gazi’s mace, the tasbih or prayer beads, birds, deer, hookahs etc, are extremely stylised. The figures of Gazi, his disciples Kalu and Manik Pir, Jama’s (the Hindu god of death) messengers, etc appear rigid and lifeless. Though there is no attempt at realism in the images of Gazir pats, the sort of painting has a time value as primitive work.

Among the adi patchitras or ancient paintings besides the Gazir pat, we also come across in history the Mahabharata pat, Ramayana pat, Muharram pat, Jam pat, Chaitanya pat, Manasa pat, Laxmi pat and others. Among the modern pats, one can see saheb pats, cinema pats and grameen pats.

Holding on to the tradition of painting Gazir pat with resilience is Shambhu Acharya of Munshiganj. His is the ninth generation of ankaiya. Shambhu, born in 28 Poush, 1362 BS (1956) at Kalendipara, Rikabibazar, Munsiganj, has learnt the art of Gazirpat from his father Sudhish Chandra Acharya. There may be other ankaiyas in other parts of Bangladesh pursuing this particular form of painting, but Shambhu has the privilege of claiming to have come from an unbroken line of patuas.

During 1980s, noted folk art researcher, Dr Tofael Ahmed saw a Gazir pat in the Ashutosh Musem in West Bengal, and read in the information that, that particular pat was the only existing pat in Bangladesh and West Bengal. After coming back to Bangladesh, Dr Ahmed started looking for Gazir pat in the rural areas. After visiting many places, Dr Ahmed, accompanied by Dr Hamida Hossain and artist Kalidas Karmakar, came to the village of Hajipur in Narshindi. There they met a huge group of bedes.

While talking about Gazir pat, with the bedes, singer Konai Mia, showed a Gazir pat rolled up in the boat. The owner of the pat, Durjan Ali, another bede singer, was not present at that time.

The team was overwhelmed with joy as they discovered a pat which would be an important link in the history of folk art in Bangladesh. When Durjan Ali came back he told them that he had bought the pat from a patuya, named Sudhish Achariya in Bikrampur (now Munsiganj) twenty years ago, in the 60’s.

Once he got the address of Sudhish, Dr Ahmed rushed to Munsiganj in search of the Acaharya and fortunately met Sudhish. But at the time the demand for pat had decreased and Sudhish had become more involved in making pratimas. Dr Ahmed pursued Sudhish to go back to painting Gazir pat, as this art was on the way of extinction.

Shambhu in his early life had learnt the art by watching his father work. But as the demand of Gazir pat fell and it became difficult to survive by selling pats. So he started earning a living by painting images of gods and goddess on the walls of Hindu temple. Shambhu even had a shop named Shilpalaya, where he used to paint signboards and banners to make ends meet.

Since his early life, Shambhu has been involved in depicting Gazir pats as a part of his familial tradition. ‘I used to help my father. At first he told me to put colours on the figures,’ said Shambhu. Shambhu used to draw different types of images on the walls of houses of his neighbours in his early life. They used to scold him, but sometimes appreciate him. Seeing his interest in paintings his father, Sudhish involved his son in this field and gave him lessons on this traditional work, which he had inherited from his ancestors. Besides depicting Gazir pats, Shambhu’s father also used to make pratimas, images of the gods and goddesses. Shambhu’s father used to use gamchha as the canvas of the pats and used brushes, made of goat hair. He himself used to make the brushes. Today Shambhu uses markin cloth as the canvas for the pats. He uses brick powder, sindur, synthetic indigo, black soot collected from the flame of oil lamps; for the canvas, powder from tamarind seeds, egg yolk, gopi mati, and different kinds of oxides.

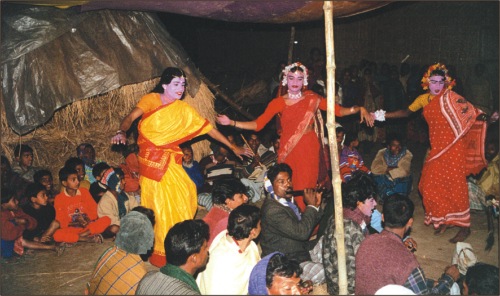

Gazir Gaan

The Fokre Paala of the Gazir Gaan (The Ascetical Drama of the Gazi Song) Dudhshar, a village in Shailkupa thana in Jhenaidaha district. There resides Rowshan Ali Jowardar, one of the lead singers or narrators (Gayen) of the Gazir Gaan (Gazi's song). The all time involvement with his performance keeps this man away from his home most of the time. In his absence, I get the address of Bhola, the leader of the troupe who resided in Bhatoi Bazar and succeed to meet him.

Gazir Gan songs to a legendary saint popularly known as Gazi Pir. Gazi songs were particularly popular in the districts of faridpur, noakhali, chittagong and sylhet. They were performed for boons received or wished for, such as for a child, after a cure, for the fertility of the soil, for the well-being of cattle, for success in business, etc. Gazi songs would be presented while unfurling a scroll depicting different events in the life of Gazi Pir. On the scroll would also be depicted the field of Karbala, the Ka'aba, Hindu temples, etc. Sometimes these paintings were also done on earthenware pots.

The Gazir Gaan singers and the instrumentalists took their seats facing north on the square shaped mat. Then commenced the starting ritual. As the lead singer implanted the symbolic icon, Gazir Asha (Hope of Gazi) north of the audience, music played on. Among the musical instruments were flutes, harmonium, juri or Mandira (a small hollow pair of cymbals) and the dhol (instrument of percussion which is not so much in width as a drum but longer in size). After the group instrumental, the lead singer presented a devotional song with his troupe accompanying him in stages.

If you come, Oh Merciful to rescue the destitute / (Merciful) Please take and make me cross

(I) do not offer my prayers, nor do I fast / Please have mercy and make me cross

(I) coming into this world / about you I have forgotten/ under the spell of infatuation . . .

There are altogether 7 Paalas (episodes) in the Gazir Gaan performance:

Each individual has the knowledge of good or bad and for the singers and the spectators or the audience of Gazir Gaan, the performance is as recreational as it is of devotion. Some show their devotion by praying, some by worshiping (Puja), some by offering a particular sacrifice to the deity on fulfillment of a prayer (Manot) and some may look for some other way to express their devotion. Gazir Gaan, whatsoever includes humour or even obscenity, ultimately it is something of sheer devotion.

1. Marriage 2. Didar Badshah 3. Dharma Badshah 4. Erong Badshah 5. Taijel Badshah 6. Tara Dakait 7. Jamal Badshah

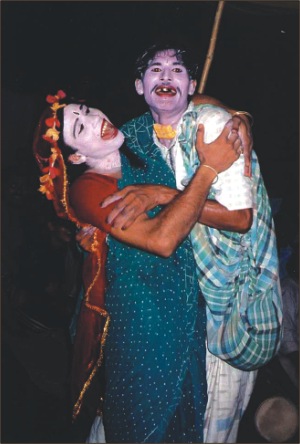

But the performance commences with the “Fokre Paala" depicting the story behind Gazi and Kalu's becoming ascetics after which continues seven episodes. Gazi is very serious and sincere in his work, while the character of his brother Kalu is more comical and he is the one who creates the humour through his role. Through his jeers and meaningless dialogue and activities he very skillfully takes the audience into the embedded sorrow and depth of the story. Here are some quotes from the "Fokre Paala". After the dance performed by the "Chukris", the lead singer stands up and delivers some introducing words in his local accent.

After the introductory words of the narrator, starts the instrumental and then the Dhua or starting chorus of the narrative passes from the lead singer to his members of the chorus.

Singer starts the main narration of the Fokre Paala of Gazi and Kalu and at the beginning he requests Kalu earnestly to become Gazi's companion in his quest of becoming an ascetic leaving behind the earthly pleasures and luxury. As this song ends Kalu comes up and takes part in dialogue (in verse and prose)based drama with the lead singer. The statements and their replies are rather nonsense, comic in nature and sometimes with the use of indecent words.

Gazi's knowledge and asks questions related to Sufi mysticism. Gazi answers satisfactorily and at one stage Kalu points out the asha of the Gazi. [The asha is one of the most holy ritual accessories that play an important role in the performance of the miracles of the saints (Pirs). It indicates the symbolic representation of a saint's supernatural power. During the Gazir Gaan performance, the asha is implanted in the ground and is not used in the performance. Other ritual accessories are used in Gazir Gaan and the offerings made to the saints in the performance are usually taken by the lead-narrator or singer himself on behalf of the saint.

At the end of the performance of each episode of the Gazir Gaan, the narrator asks the crowd which episode would they like to watch. The troupe performs accordingly because it is the mood of the crowd that matters to really feel the beat of the performance (Saymon Zakaria, August 30, 2004). .

Among the indigenous Bangalee art forms, pata-chitra or scroll paintings stand apart in their choice of subjects, vibrant colours, unique lines and style of presentation. Painters of this form are called patua. An exhibition of traditional pata-chitra by three patuas, Dukhushyam (Osman) Chitrakar, Rabbani Chitrakar and Rahim Chitrakar, is being held at DOTS Contemporary Arts Centre on Tejgaon-Gulshan Link Road. (Daily Star, April 9, 2006).

The term Pata is derived from the Sanskrit word Patto, meaning cloth. In ancient times, before paper was introduced, artistes used to paint on thick cotton fabric. Usually mythical or religious stories were the themes. However, in time contemporary issues, animals and more found their place on these painting. "Pata-chitra is perhaps the oldest art form in the Indian subcontinent and the tradition continues to this date. In fact, the art form can be traced all the way back to sixth BCE."

Besides being visual delights, the scroll paintings are also used in pat gaan or patua gaan. Through the medium of scroll painting, a choir narrates a story. Most of the paintings in the exhibition illustrate myths, episodes from the Purana, Ramayana; some feature animals and imaginary monsters. The paintings have several sections so as to maintain a sequence. In the first segment the main characters, usually Gods and Goddesses, are portrayed boldly. A painting featuring Raashleela of Radha-Krishna is stunning. Snake-like creatures with three heads on another one are interesting. Another painting shows three gruesome rakhkhoshi (females monsters) in their "full glory" -- teeth shaped like carrots sticking out, talons sharper than an eagle's -- staring back at the viewer as if to warn them to keep a safe distance.

Goddess Durga is the subject of several scrolls. One of the paintings show the Goddess smiting the beast Mahishashur. Vibrant colours -- yellow, indigo, bottle green, khaki, crimson and dark brown -- create a dazzling effect. Four Gods and Goddessess -- Ganesh, Karthik, Lakshmi and Saraswati -- ornate the corners of the painting. The story of Goddess Kali stamping on God Shiva is the subject on a scroll. The Goddess is bare, as she is portrayed traditionally and painted in deep purple. In episodes from the Ramayana, Rama and Sita are seen getting married in the first segment. Other scenes featured are Lakshman cutting the nose of the monster, Suparnekha and Sita abducted and imprisoned by Ravana. An interesting scroll shows fish carrying other fish in paalkis.Bangladesh is home to long and rich folk tradition. Dr. D. P. Ghosh (1980) says, "two thousand and five hundred years ago, scroll painting or panel painting was widely used in this country." The art of Bangladesh influenced the art of the Far-East, especially the art of Java. In Bangladesh, folk painting is a part of vast folk culture, developed from time immemorial (Prof. R. Alam,2001).

The patuas are artisans, who are now principally engaged in decorating pottery which is also a dying craft. Now a days we do not find any Patua in one time famous Patua colonies of Bengal.

In Bengali Chal Chitra (inverted shaped roof like design) are employed on the clay images. Chal Chitra are done by the village folk artists. This has become a dying art.

Ghat means water pitcher in Bangla. Manasa is the snake goddess. These ghats are made from clay on the potter's whell and then dried and burnt. All the Ghatsare absolutely folk in nature and primary colours are bold draughtsmanship are employed. The style of painting has affinity with ancient Egyptian and Minoan painting, especially in the depiction of eyes.

Potchitro or story telling through depicting images on canvas has always been a traditional form of art and entertainment. The trail goes a long way back to the Middle Ages when story telling was an important form of entertainment in Bengal. Poets told tales of gods, saints and the virtuous, of kings and queens, through their writings. Artists portrayed these verses through colours and motifs. The age-old folk art survived centuries to tell the tale. It still continues to entertain the art enthusiasts.

The exhibition displays 45 pieces of Raghunath's work depicting everyday life of the rural people and the popular motifs of Bengal. Raghunath Chakravarty does not have any academic training. He did however found inspiration from his mother and later on from renowned potchitro artist Shambhu Acharya. The stroke of the brush came to him naturally.

“I learned from my mother. She used to paint potchitro and decorate the house with alpona whenever there was an occasion”, he said. “From then on I had colours in my mind. I just started to compose in my head and started with a brush one day”, he added.

Raghunath however personalised the art. From religious stories he moved on to everyday life of the rural people. From traditional practice of story telling on clay pots he moved to canvas. “I find it more attractive the lives of the ordinary folks, everyday struggle, the beauty of the rural landscape”, said Raghunath. Raghunath's favourite theme is the eternal love between mother and child. In his work the theme keep coming back along with boat race, the weavers and the carpenters at work, rural wife's cooking preparation, the bangles seller lady, women fetching water, ethnic women at work and many more (S. Parveen, October 24, 2007).

No comments:

Post a Comment